The inspiration and motivation to share this website is founded on the loss of Steve and of Maria Hance - may their memories be a blessing to many.

Panic Kills: The Deadly Cost of Losing Control -> Don’t Get Dead

In the high-stakes game of survival, one simple truth has guided me through some of life's most terrifying moments: "Panic kills." This motto isn't just a catchy phrase; it's a hard-earned lesson forged in the crucible of personal peril. I've seen it play out firsthand—once during my first certification scuba dive when I ran out of air at 100 feet below the surface, again when my three-year-old son, who couldn't swim, fell into our pool and floated face down, perfectly still, until I pulled him out, and most profoundly, during two dark periods when I contemplated and planned suicide amid overwhelming panic. These experiences underscore a profound reality: panic doesn't just heighten danger; it often creates it. In this article, we'll explore how panic operates as a silent assassin, drawing on psychology, physiology, real-world examples, and survival theory to illustrate why staying calm isn't just advisable—it's essential. By expanding on my stories and weaving in broader insights, including a return to aviation, we'll uncover the mechanisms of panic and strategies to combat it, aiming to equip you with the mindset to thrive in crisis. Especially on a suicide prevention platform like this, remember: if you're in crisis, reach out—help is available (the suicide hotline 988 is available 24 hrs/day 7 days/week, and saved Ron’s life – see the interview with him), and hope is real, there are people who care about you, and you can always wait till another day.

The Anatomy of Panic: A Biological Betrayal – What it is, How it Kills

To understand how panic kills, we must first dissect what panic is. At its core, panic is an extreme manifestation of the fight-or-flight response, a primal survival mechanism hardwired into our brains. When faced with a perceived threat, the amygdala—the brain's alarm center—triggers a cascade of physiological changes: adrenaline surges, heart rate skyrockets, breathing becomes shallow, and blood flow redirects to major muscle groups. This prepares us for immediate action, but in modern crises, it can backfire spectacularly.

Psychologist Daniel Goleman coined the term "amygdala hijack" to describe how this response overrides rational thinking. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for decision-making and impulse control, gets sidelined, leaving us prone to impulsive, often disastrous choices. Physiologically, panic induces hyperventilation, which disrupts oxygen-carbon dioxide balance, leading to dizziness, tunnel vision, and muscle fatigue. In extreme cases, it can cause cardiac arrest or exacerbate underlying health issues. Theory from evolutionary psychology suggests this response evolved for short, acute threats like predator attacks, not the prolonged, complex dangers of today—drowning, car crashes, natural disasters, aviation emergencies, or even internal battles like suicidal ideation—where clear-headedness is key.

Gavin de Becker, in his seminal book The Gift of Fear, argues that true intuition (a calm assessment of danger) saves lives, while fear escalated into panic destroys them. Studies from the field of survival psychology, such as those by John Leach in Survival Psychology, reveal that in disasters, 10-20% of people freeze, 70-80% behave irrationally due to panic, and only 10-20% act effectively. This "disaster syndrome" highlights how panic doesn't just impair individuals; it can cascade into group failures, amplifying catastrophe. In mental health crises, this dynamic is even more insidious, as panic distorts perception, turning temporary despair into seemingly permanent hopelessness.

My Scuba Dive Ordeal: A Descent into Potential Doom

Let's revisit my first personal encounter with this truth. As a 15-year old novice diver pursuing certification, I descended to 100 feet in an old flooded quarry, my first dive out of the YMCA swimming pool, the weight of the 100+ feet of water above me pressing down like an invisible vice. Everything was going smoothly until I was not getting any air as I sucked on my regulator. Bubbles ceased, and the regulator delivered nothing but silence. In that moment, the temptation to panic was overwhelming: thrash upward, gulp for air that wasn't there, or signal wildly to my dive buddy.

But I remembered my training: panic consumes oxygen faster, turns a solvable problem into a fatal one. The fact that I was with a buddy, for safety, someone I trusted, was key to suppressing fear and panic. Many years later, the panic attacks of my mother with her COPD highlighted how much fear and panic enters, when there is difficulty breathing. Instead of panic, I stayed calm, signaling my buddy with deliberate hand gestures. We shared his alternate air source and ascended slowly, avoiding the bends (decompression sickness) that rapid panic-induced surfacing could cause. Had I panicked, I might have bolted for the surface, risking embolism or drowning from exhaustion. Decompression theory explains why: at depth, nitrogen dissolves into tissues under pressure; a panicked rush up causes it to bubble out like opening a soda bottle, potentially blocking blood vessels and causing strokes or death.

This isn't hypothetical. The Diving Alert Network reports hundreds of scuba fatalities annually, many linked to panic. A 2018 study in Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine found that 41% of diving deaths involved panic as a contributing factor, often leading to poor decisions like abandoning buddies or ignoring equipment protocols. My experience taught me that panic kills by eroding the thin margin for error in high-risk situations and activities, turning manageable mishaps into tragedies.

My Son’s Pool Incident: Innocence Meets Instinct

and the Swiss Cheese Lines Up to Provide a Miracle

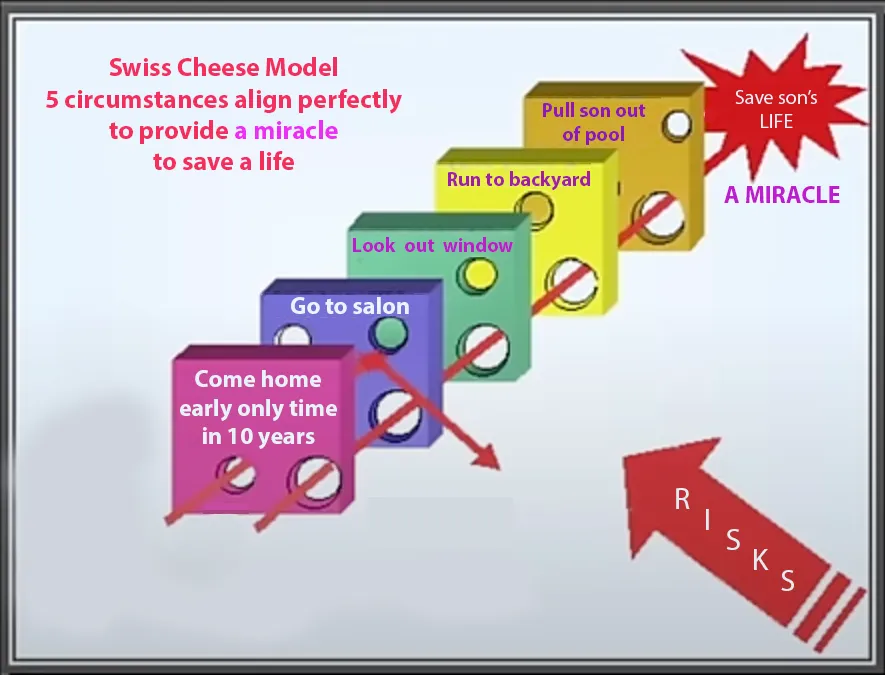

Contrast that with my 3-year old son Matt’s brush with death, a stark illustration of how the absence of panic can be lifesaving—even in the very young. At three years old, he couldn't swim and had no formal water safety training. One sunny afternoon, he tumbled into the deep end of our pool while I was arriving home early from work, the only time in 10 years I left work early, while my wife was talking to a neighbor. When I arrived home, I went down into the salon, not my normal process, looked out the window, saw the pool fence gate open, ran down and out into the backyard, found my son floating motionless, spread-eagled in the pool. I pulled him out and turned him over, he opened his eyes, with a look on his face like “am I in trouble?” But his lips and face were not blue, he started breathing normally, without coughing up any water.

I’m showing here a graphic of the Swiss Cheese model for aviation accidents, originated by James Reason, to illustrate that the majority of aviation accidents occur due to a series of failures, each passing a series of normal barriers, the individual barriers represented by parallel slices of swiss cheese. My thanks to Juan Browne of the blancolirio YouTube aviation channel, who gave me permission to modify his Swiss Cheese graphic. Juan indicates 5 normal barriers that must all be bypassed to arrive at an accident. I turned that around to show 5 circumstances that lined up to provide a miracle that allowed me to save my 3-year old’s life. In reality, I would propose there were 2 more circumstances, 7 in total, as there was Matt’s lack of panic, and a friend explained to me that for Matt to not have swallowed water and not appear blue, I had to arrive within a 20 second window from his fall into the pool.

Swiss Cheese Model - Disaster or Miracle?

Thanks to Juan Browne, of the blancolirio YouTube aviation channel, who gave me permission to modify and use his Swiss Cheese Model of aviation accidents.

In my case, rather than a series of protective barriers being breeched to end in disaster, I had a series of "circumstances" line up perfectly to produce a miracle that allowed me to save my 3-year-old son Matt's life.

I really should add two more slices of cheese: one for the fact that Matt did not panic, and another for the fact that I arrived within a 20 second window for him not to have breathed or swallowed any water.

It was instinctual non-panic. Children that age often lack the cognitive framework for full-blown fear; instead, they might default to a "playing dead" response, conserving energy. Experts in pediatric drowning prevention, like those from the American Academy of Pediatrics, note that drowning is silent—panic-induced thrashing is rare in toddlers because their underdeveloped motor skills and limited understanding prevent it. Yet, if he had panicked, struggling could have exhausted him faster, leading to quicker submersion and aspiration of water. In the case of drowning adults, panic and wildly flailing in the water is more common. Lifeguards are instructed to approach a panicked person from behind, to be able to take hold without being grabbed in panic, which has on occasion led to the drowning of both the victim and the lifeguard.

This mirrors broader drowning statistics: the World Health Organization estimates 236,000 drowning deaths yearly, with panic playing a role in many adult cases. Survivors often credit calmness—floating to conserve energy, as my son inadvertently did. In Deep Survival by Laurence Gonzales, the author discusses how panic overrides survival instincts, citing cases where swimmers exhaust themselves fighting currents instead of swimming parallel to shore. My son's stillness was an accidental masterclass in survival: by not panicking, he bought precious time.

My Swiss Cheese Model

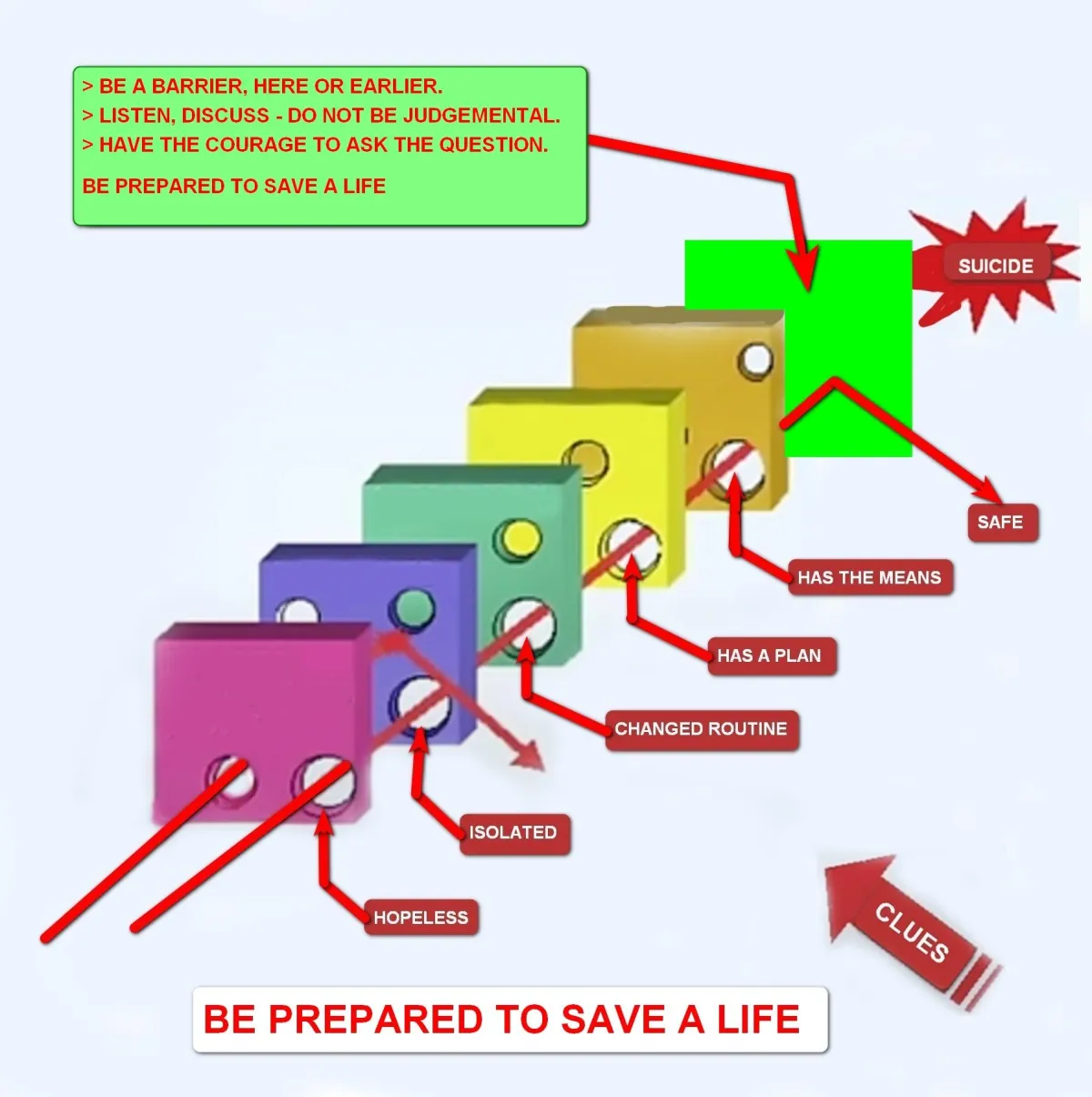

on Being Prepared to Save a Life

Be a Barrier, and the Earlier, the Better

Here the slices of cheese represent clues

Clues of struggles:

Feeling Hopeless

Feeling Isolated

Has Changed Routine

Has a Plan for Taking Their Life

Has the Means to Act on the Plan

Sealing. the Holes:

Encouraging

Intentional Listening

Providing a Safe Space

Not Judgemental

Separate From the Means

Willing to call 988 for fHelp

When Panic Turns Inward: My Two Battles with Suicidal Thoughts

The most intimate and harrowing applications of "panic kills" come from my own mental health struggles. There were two periods in my life when I found myself thinking about and planning suicide, each time engulfed in a storm of panic. I felt utterly hopeless, trapped in a pessimistic vision of my future that I now know was distorted and incorrect, impacted by some who encouraged me to harm myself. In those moments, panic amplified every negative thought: career concerns became insurmountable ruins, relationship strains felt like eternal isolation, and false accusations loomed as unchangeable destinies. My mind raced, convinced that ending it all was the only escape from an imagined hopeless lifetime of suffering.

Panic, in this context, acted like a mental fog, hijacking my ability to see reality or alternatives. I catastrophized, believing my problems were permanent when they were, in fact, temporary. Research from the American Psychological Association shows that suicidal ideation often peaks during acute panic states, where cognitive distortions—such as overgeneralization and black-and-white thinking—dominate. A study in JAMA Psychiatry links panic disorders to a 10-fold increase in suicide risk, as the physiological arousal (racing heart, shortness of breath) reinforces feelings of doom, making impulsive actions more likely.

But here's the turning point: in both instances, a sliver of calm broke through. The first time, a specific sound flipped a switch in my mind and interrupted the spiral, reminding me of connections I had overlooked, and the fact that I did not have to take a permanent action in that moment, on that day. The second time, I connected with a Christian counselor who deeply resonated with me, where a compassionate voice helped me breathe through the panic and reframe my fears. For some reason I found it difficult to believe the reassurances of family – “they’re just saying that” – but could trust the honesty of the counselor. These interventions showed me that panic's predictions are often wrong—my future wasn't the bleak void I envisioned; it held recovery, growth, and joy. Today, as someone who survived those dark times, I share this to emphasize: suicidal thoughts thrive in panic's shadow, but seeking help—whether through therapy, support networks, or hotlines like the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (988 in the US)—can dispel it. You're not alone, and the future you fear may be brighter than panic allows you to see.

Fear and Panic: pull up, raise the nose

vs

Correct Action: lower the nose to gain speed and recover

These personal anecdotes are not isolated; history and headlines brim with examples where panic proved lethal, as well as examples of when overcoming fear and panic saved lives. Let’s return to aviation disasters, and near-disasters. There are no coincidences in my life – not 39 years ago when I saved Matt’s life, not this last week of August 2025, putting the finishing touches on this website to help prevent suicide. Two YouTube aviation videos came up in my feed.

First there was “Spin, Spin, Spin!” from blancolirio. This was the story of a student and instructor in a sailplane in New Zealand. The student is sitting in the front and evidently had some experience as a pilot in powered aircraft. They find themselves in a downdraft and clouds, disoriented, enter a “classic graveyard spiral” from the disorientation of having no visual references.

The student sailplane pilot has better visibility and announces he has control. When they break out of the clouds they are just above the trees as they spiral down. The natural impulse, with the normal fear and panic, even from an experienced pilot, would be to pull back, to point the sailplane back upwards. But this student pilot remained calm enough to remember that to recover from the spin, he had to lower the nose, not raise it, to gain some speed to be able to recover. It was a very close call, but he was able to recover.

The same day, watching the “Near Death Experience” and The Danger of EGO! Episode of the Captain’s Speaking – The Mentour Pilot Podast, with Petter Hornfeldt and Ben Watts, there was a very similar story. Ben recounted the time that was “the closest he has come to being scared in an aircraft.”

Twenty-odd years ago as a new flying instructor he would provide introductory flights to people interested in becoming a pilot. It was a very busy, very hot summer day, and for his fifth and final flight of the day they gave him a different airplane, a little older and less powerful. He started his takeoff roll on a grass runway with a row of trees just past the runway, to return to the base airport. But when he gets halfway down the runway he can see that the airspeed is low and he performs his first ever rejected takeoff.

They go back to the end of the runway to try again, with a different process, he applies full power with the brakes on and gives the engine time to gain power, releases the brakes and starts his roll. He knows he needs to get to 55 knots rather than 65 to get airborne with his new process. Halfway down the runway, he is only at 45 knots and has to decide whether to continue.

With a healthy dose of “press-on-it is” and “carry-on-it is” he decides they’ll do it this time. It’s a decision he regrets immediately after, when it was now too late to change his mind. As he approaches the tree, the airplane is close to stalling. Just like the sailplane in New Zealand, the natural impulse, fueled with fear and maybe panic, is to pull back and raise the nose to get over those trees.

But Ben lowered the nose to gain airspeed, raised the flaps and climbed away. It was a very close call, which anyone with any flying knowledge would realize. When Ben looked at the passenger, he was clueless, snapping photos, no idea how close they had come to an accident.

Another Two Aviation Examples of Not Panicking

In the 1989 United Airlines Flight 232 crash, the plane lost all hydraulics, yet Captain Al Haynes and his crew stayed composed, crash-landing in Sioux City, Iowa, saving 185 of 296 aboard. Haynes later attributed survival to avoiding panic, methodically troubleshooting, despite the odds.

Aviation safety expert Chesley "Sully" Sullenberger, hero of the 2009 Hudson River landing, emphasizes in his writings that panic impairs the "startle response," delaying critical actions by seconds that mean life or death.

An Aviation Example of Panic Leading to Tragedy and Death

Conversely, the 2018 Lion Air Flight 610 plunged into the sea after pilots panicked amid faulty sensor data, overriding automated systems incorrectly—killing all 189.

Even in everyday scenarios, panic kills.

Road accidents spike when drivers swerve erratically in panic rather than braking steadily. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration links thousands of U.S. crashes yearly to "overcorrection" born of panic. In mental health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that suicide rates rise during economic panics or personal crises, underscoring how internal turmoil mirrors external ones.

Combating Panic: Tools for Survival

So, how do we counter this killer? Theory and practice converge on preparation. Mindfulness training, like that in cognitive behavioral therapy, rewires the brain to delay amygdala hijacks. Let's dive into specific techniques that anyone can practice to build this resilience, especially useful in moments of rising panic or suicidal thoughts.

One foundational method is box breathing, a simple yet powerful tool used by Navy SEALs: Inhale deeply through your nose for a count of four, hold your breath for four counts, exhale slowly through your mouth for four counts, and hold again for four. Repeat this cycle for a few minutes. It restores oxygen balance, slows your heart rate, and pulls you back to the present, interrupting the panic spiral.

Another effective technique is the 5-4-3-2-1 grounding exercise, which engages your senses to anchor you in the now. Name five things you can see around you, four things you can touch, three things you can hear, two things you can smell, and one thing you can taste. This shifts focus from racing thoughts to immediate reality, reducing the intensity of hopelessness or fear. It's particularly helpful during suicidal ideation, as it creates space for rational thinking.

Body scan meditation involves lying or sitting comfortably and mentally scanning your body from head to toe, noticing areas of tension without judgment. Start at your scalp, move down to your toes, and breathe into tight spots, releasing them on the exhale. Apps like Headspace or Calm offer guided versions, and research from the University of Massachusetts Medical School shows it reduces anxiety by 20-30% with regular practice.

Mindful walking encourages slow, deliberate steps while focusing on the sensation of your feet hitting the ground, the rhythm of your breath, and your surroundings. Even a five-minute walk can disrupt panic by promoting mindfulness of the body in motion, fostering a sense of control.

Loving-kindness meditation (metta) builds compassion: Repeat phrases like "May I be safe, may I be healthy, may I live with ease," then extend them to others. Studies in Journal of Clinical Psychology indicate it decreases self-criticism, a common trigger for suicidal thoughts, by enhancing emotional regulation.

Progressive muscle relaxation entails tensing and then relaxing muscle groups sequentially—clench your fists for five seconds, release, then move to your arms, shoulders, and so on. This releases physical tension tied to panic, promoting calm.

Military and first-responder programs, like the U.S. Navy SEALs' "mental toughness" training, simulate stress to build resilience, teaching that panic is a choice thwarted by habit.

Visualization and scenario planning, as advocated by de Becker, help: rehearse crises mentally to normalize them. Education is key—knowing facts, like the "rule of threes" in survival (three hours without shelter, three days without water), prevents panic by providing a roadmap. For mental health, building a support system and practicing gratitude can counteract pessimistic distortions. Incorporate these techniques daily; consistency turns them into automatic responses during crises.

Conclusion: Embrace Calm, Defy Death – Don’t Get Dead

"Panic kills" isn't hyperbole; it's a mantra backed by biology, history, and hard experience. From my airless depths to my son's silent float, and through my own suicidal panics, I've witnessed how composure carves paths to safety amid chaos. By understanding panic's mechanisms—its hijacking of reason, exhaustion of the body, and amplification of errors—we can arm ourselves against it. Whether in oceans, skies, daily life, or the depths of despair, the choice to stay calm isn't innate; it's cultivated. Adopt this motto, train your mind, and remember: in the face of fear, panic is the real predator. Survival favors the steady—may you always choose calm over catastrophe. If you're struggling, please call a hotline or seek professional help; your story can still have a hopeful ending.

Please Help Us Spread the Word

[1] - Please watch the 7 minute video at the top of the Home

page all the way through and like it, the share it on social media.

The link is: https://youtu.be/mfxI7o3imZc

[2] - Also please share the link to this Home page:

https://bepreparedtosavealife.com

[3] - Finally, for those who like and have friends who like the

Riswue, Please share the video going into the men's room to

see the poster:

© 2024 Be Prepared To Save A Life